Inhalte dieses Wikis:

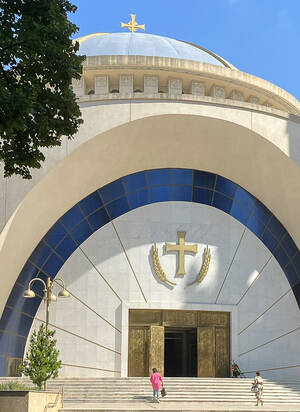

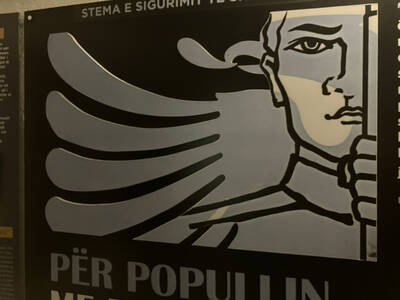

Der Osten des Westens

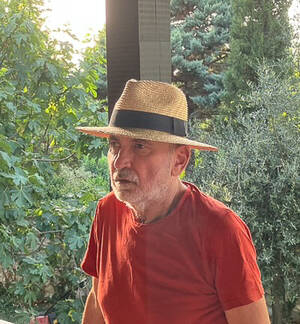

Stefan Budian

Was ist ein "Schatzbild"?

Galerie

Reisebetrachtungen

Finanzierung

Administration

Weitere Wikis:

Worldmap-Wiki

hier: Nachbarschaft im Innenhof

Kontakt und Impressum:

Kontakt zu Stefan Budian

Impressum und Datenschutz

Zur Startansicht des Computerspiels „Worldmap“: